Death Squads in America

1. The Reality of Police Surveillance in Cleveland

Over the past several years, Cleveland has embraced a suite of modern surveillance tools that sit at the intersection of public safety and civil liberties. The city has installed at least 100 fixed automated license plate reader (ALPR) cameras at major intersections — a system costing roughly $250,000 — with plans for hundreds more, including in-car ALPR units that will only go live once a final policy is enacted. These devices automatically scan passing vehicles, log plate images, and cross-reference them with law enforcement databases to flag stolen cars, Amber Alerts, and other alerts.

Cleveland also utilizes ShotSpotter gunshot detection sensors and other listening tools, and discussions continue about drones and real-time crime monitoring hubs. Civil liberties advocates, residents, and some researchers have raised alarms about these deployments — noting uneven accuracy, privacy risks, and disproportionate impact on minority neighborhoods.

Despite reassurances from police leadership that tools like ALPR cameras are used “to look at vehicles, not people,” questions persist over transparency: the department has declined to make camera locations public, and critics argue that data retention policies and access controls remain vague.

2. Surveillance Tech Meets Structural Inequality

Nationwide, AI-powered policing is rapidly evolving, but not without controversy. Law enforcement agencies across the U.S. have integrated tools such as:

- Automated license plate readers (ALPRs) — capture extensive plate data, GPS metadata, and timestamps for databases that can be searched and cross-referenced.

- Predictive policing algorithms — systems that analyze historical data to forecast future crimes or hotspots, often drawing on arrest patterns, socioeconomic inputs, and past patrol allocations. Critics call these systems a “self-fulfilling prophecy,” where racially biased historical data leads to more policing in certain neighborhoods — and then more arrests.

- Facial recognition software — used to match individuals in police footage against massive image databases, often with higher error rates for women and people of color. A notable example includes Clearview AI, a controversial private company supplying such software to law enforcement agencies.

- ShotSpotter and acoustic sensors — alert police to potential gunshots but have been criticized for false positives and unproven public safety benefits.

These technologies promise precision and efficiency, yet two consistent themes emerge from researchers and watchdogs: bias and lack of transparency. AI systems are often trained on historical police data — data that reflects existing disparities in policing and arrests — embedding patterns of discrimination into their decision-making.

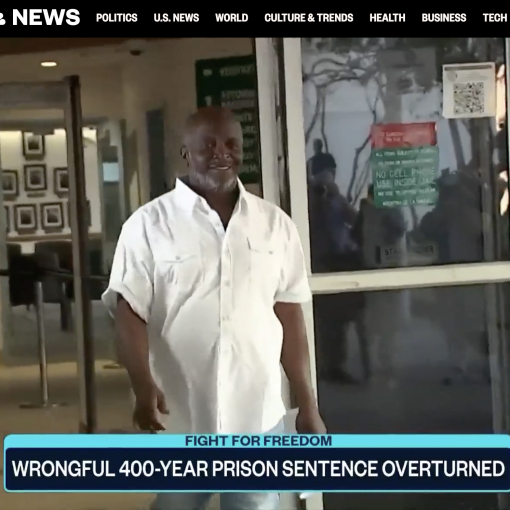

In both predictive analytics and facial recognition, tests have shown that algorithms may disproportionately misidentify certain demographic groups — especially Black individuals and women — raising the specter of wrongful arrests grounded in flawed machines.

3. Judicial AI: Efficiency vs. Fairness

AI’s footprint isn’t limited to patrol cars and street corners — it’s also creeping into courtrooms and pretrial assessments. Tools like COMPAS and other risk assessment algorithms are used to guide decisions about bail, sentencing, parole, and probation. Proponents see efficiency gains and standardized evaluation; critics see a digital echo of centuries of bias that could undermine equal protection and due process.

Beyond bias, the so-called “black box” nature of many AI systems — where neither defendants nor lawyers can meaningfully understand how an algorithm reached its conclusions — heightens concerns about accountability and constitutional rights. Public perception studies also indicate that if citizens view AI as opaque or unfair, overall confidence in the justice system can erode — even if algorithms were neutral in theory.

4. Community Trust on the Line

Across cities that have deployed widespread surveillance technology, civil liberties organizations — including the ACLU and local community groups — stress that without clear safeguards, oversight, and public participation, the same tools meant to protect can become instruments of disproportionate surveillance.

In Cleveland’s case, a surveillance oversight committee has been convened and promises a review of policies before new systems go live. However, skepticism remains over whether these bodies will have sufficient authority to constrain data retention, ensure audits for bias, or compel disclosure of technology usage.

5. Enter GoVia Highlight A Hero — A Potential Paradigm Shift

Amid the tension between expansive surveillance and justice, GoVia Highlight A Hero proposes a different paradigm — one centered not on automated profiling, but community-informed police accountability.

Unlike predictive analytics or opaque surveillance systems, GoVia’s model is designed to:

- Empower community reporting: Users can submit verified and respectful feedback on police encounters, allowing citizens to highlight positive interactions and concerns alike.

- Facilitate transparency: Features like instant generation of subpoenas for bodycam footage and GPS-verified interaction logs (aligned with Cleveland’s broader police reform goals under its Consent Decree) help to document encounters in real time.

- Enhance crisis support: Integrated access to emergency medical and mental health assistance aims to reduce escalation in encounters involving vulnerable populations, addressing long-standing gaps in crisis response.

- Build civic trust: By enabling community voices — including praise for officers who exemplify fairness — GoVia seeks to rebalance the narrative around policing beyond surveillance alone.

Where traditional AI policing can aggregate data to predict suspicion, GoVia’s framework aggregates verified community experience to affirm accountability. This flip — from prediction to participation — could recalibrate power dynamics in law enforcement encounters and reduce reliance on technologies with documented bias risks.

6. A Path Forward: Accountability, Oversight, and Innovation

Cleveland’s experience reflects a national crossroads: technological capability is racing ahead of governance structures and social trust. License plate readers, ShotSpotter, facial recognition, and predictive tools can aid investigations, but without robust transparency, regular audits for bias, meaningful civilian oversight, and legal safeguards, these systems risk becoming engines of inequity rather than justice.

Platforms like GoVia — embedded with community feedback loops, legal documentation tools, and real-time accountability mechanisms — illustrate how innovation can be harnessed for procedural justice rather than mass surveillance.

In a justice system strained by mistrust and technological upheaval, the imperative is clear: policies and platforms must be grounded in equity, oversight, and human dignity — not just efficiency or data collection.